By Brent Engel

Contributing writer

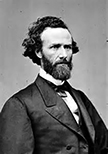

A Pike County legislator took an active role in the 1866 debate over a constitutional provision that’s being cited today in accusations against former President Donald Trump.

Missouri U.S. Sen. John Brooks Henderson of Louisiana was heavily involved in 14th Amendment deliberations. Most of his arguments centered on giving voting rights to black people freed from slavery after the Civil War.

But he also addressed the ambiguous section that bans people who’ve taken a constitutional oath from holding civil office if they “have engaged in insurrection or rebellion” against the government or “given aid or comfort” to its enemies. Congress can remove the penalties with a two-thirds vote in each chamber.

Trump has not been charged with insurrection, let alone convicted of it, but does face 91 federal and state allegations in four indictments.

The case relevant to the 14th Amendment stems from his alleged role in violence at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. He’s accused of conspiracy and obstruction.

The controversial move is unprecedented. Section 3 of the 14th Amendment has never been used to keep someone from becoming president. Its original intent was to prevent former Confederates from holding public office. However, many have argued it violates another part of the constitution that bans laws, which retroactively set some sort of punishment.

Confederate President Jefferson Davis invoked the section in his 1868 defense against treason charges, but President Andrew Johnson pardoned former rebels before the case was resolved. Davis, who died in 1889, was given amnesty posthumously by President Jimmy Carter in 1978.

Congress in 1872 and 1898 removed some penalties for violating the section, but courts as recently as 2022 have issued opposite rulings on questions of application for provisions that remain.

Socialist Victor Berger of Wisconsin was removed from Congress in 1919 after being convicted of espionage, but the Supreme Court overturned the verdict in 1921 and he served for six years.

Henderson, the catalyst behind the 13th Amendment outlawing slavery, could not have envisioned using the constitution to keep a presidential candidate off the ballot. However, his words about voting rights indicate he probably would have rejected the idea.

In a speech to Senate colleagues, the Republican said that “even the worst rebel leaders” should not be denied the freedom to choose candidates, and that attempts to do so should be “wholly abandoned.”

“We must be merciful,” he said. “I am willing to make the highest virtue of that necessity.”

The words came with a caveat. Henderson had no problem ousting what he called “traitors”—but only if duly convicted of crimes against the nation.

“If it were proposed to take from them life, liberty or property, I would be unwilling to do so except according to the law of the land,” he said. “But when it is only proposed to fix a qualification for office and deny them future distinctions, which would rather make their treason honorable than odious, I do not hesitate to act.”

In addition, the irony of former Confederate states rejoining the Union and asking for restoration of the right to vote while trying to deny it to blacks was not lost on Henderson. In today’s context, his words could be interpreted as an effort to quell disenfranchisement.

“They clamor for suffrage, and I for one am willing to grant it to them if they will now be generous enough to extend it to all who carried the musket to defend the government while they carried the musket to destroy it,” he said.

Henderson could be accused of straddling the fence, but his overriding message became clear in another part of the speech. As he always had, the senator put abiding faith in the will of the American people rather than the manipulations of Congress or courts.

“Where all men are interested in the government, none but peaceful revolutions are needed,” Henderson said. “Reforms are worked at the ballot box. Government then, and only then, becomes a divine institution.”